Peruvian archaeology once again captivated the world in 2024 with groundbreaking discoveries that highlight the extraordinary cultural achievements of ancient peoples across the coast, highlands, and Amazon. These findings have garnered international attention and are considered among the most significant globally last year.

Here are the most notable archaeological discoveries in Peru for 2024, enriching the country's tangible and intangible heritage while offering deeper insights into the remarkable achievements of its ancient inhabitants.

1) Ancient Peruvians consumed more vegetables

In January, a study on the remains of 24 individuals found in the burial sites of Wilamaya Patjxa and Soro Mik'aya Patjxa, in Puno, revealed that early Andean inhabitants’ diets comprised 80 % plant-based foods and 20 % meat.

The isotopic analysis, conducted by archaeologists from the University of Wyoming led by Randy Haas, suggests redefining early Andean populations from "hunter-gatherers" to "gatherer-hunters."

“All credible subsistence models indicate that plant foods made up the majority of individual diets, with meat playing a secondary role. These findings contradict the hypothesis of a predominantly meat-based diet and instead suggest a primarily plant-based diet among the early Andean populations,” the study notes.

2) Monumental structure identified in Quebrada del Oso

In January 2024, archaeologists revealed the discovery of a monumental administrative building called “La Audiencia” (The audience), similar to those found in Chan Chan and other key constructions of the Chimú kingdom. The discovery was made at the Quebrada del Oso (Bear’s ravine) archaeological site, located in Chicama district, Ascope province, La Libertad region.

Carito Tavera, co-director of the Chicama Archaeological Program (PRACH) at the National University of San Marcos, led the excavation team. In an exclusive interview with Andina News Agency, she explained that this discovery prompted a reevaluation of the Chimú kingdom's occupation and administration of the valley, which was later absorbed into the Inca Empire.

“This is why we decided to work at Quebrada del Oso—it is an iconic site for Chimú occupation and administration,” Tavera emphasized.

The archaeologist noted that they focused on Structure No. 2, one of three monumental buildings at the site. This structure had not been previously excavated, despite initial investigations at Quebrada del Oso dating back to the 1970s, which were conducted by American archaeologists. “No other research team had returned to this site since then,” Tavera added.

She highlighted that the Chimú built Quebrada del Oso to expand their agricultural frontier in Chicama and ensure a greater food supply. The Intervalle Canal, constructed to transport water from the Chicama Valley to the Moche Valley, was a critical component of this endeavor. The settlement of Quebrada del Oso was established at the base of this canal.

“La Audiencia,” the largest of the three identified structures, served as a rectangular administrative space where Chimú officials gathered to make political and administrative decisions.

“There was uncertainty about whether a structure like ‘La Audiencia’ existed at Quebrada del Oso, but we hypothesized that such a space was present. This year, our complete excavations confirmed it,” Tavera concluded in 2024.

3) Enclosed structure form the Formative Period discovered in Apurímac

Peruvian archaeologists have uncovered a white-plastered structure from the Formative Period at the upper section of the Rurupa ceremonial temple, located in the district of Ancohuallo, Chinceros province, Apurímac region.

The discovery, announced in February, was led by archaeologist Edison Mendoza, a professor at the School of Archaeology and History of the National University of San Cristóbal de Huamanga.

The excavation revealed two distinct construction phases. The first corresponds to the Middle Formative Period (1,000–800 BCE), featuring a rectangular platform with a three-step staircase.

At the upper section of the site, three rectangular structures were built, including an antechamber leading to two equidistant, independent spaces with doorways.

“What stands out is the white plaster coating on these structures, later painted in various colors such as gray, brown, and reddish tones. This type of architecture is very rare in the Andean highlands and more commonly associated with coastal sites, suggesting contact with coastal cultures,” Mendoza explained in an exclusive interview with Andina News Agency.

Mendoza noted that, due to its location at the temple’s uppermost section, the structure likely served as a special space for ritual activities. “Inside one of these spaces, we discovered a rectangular altar on which the skull of a guinea pig was found. In contemporary times, guinea pigs are not only considered food but also linked to ritual practices,” he detailed.

The second phase of the site corresponds to the Late Formative Period (800–400 BCE). Some structures from this phase were covered with soil and stone fill, while the temple itself was expanded both horizontally and vertically. Construction techniques evolved from the use of small stone blocks to much larger ones.

A sunken square platform was built at the top, connected by two-step staircases on its sides. According to Mendoza, these architectural changes symbolize the emergence of a new ideology. However, the associated ceramic artifacts remain undefined and are still under analysis by specialists.

4) 5,000-year-old megalithic plaza in Cajamarca

In February, it was revealed that the circular megalithic plaza located at the Callacpuma archaeological site, Cajamarca region, is at least 5,000 years old, making it the oldest example of ceremonial megalithic architecture in the northern highlands of Peru.

"This is an early example of collective construction, places, and social integration among the Andean population, representing the cultural development of the Cajamarca region over 5,000 years, from the Late Preceramic period to the present," stated Peruvian archaeologist Patricia Chirinos Ogata, co-director of the Callacpuma Archaeological Research Project.

In an interview with the Andina News Agency, the researcher emphasized that the monumental megalithic architecture expressed in Callacpuma's circular plaza reveals a construction method never before reported in the Andes and distinct from other monumental circular plazas in the region.

"We present three radiocarbon dates associated with the initial construction of the plaza, which average approximately 2,750 years before the present, directly corresponding to the Late Preceramic period, when the first monumental constructions in the Andes emerged. This is one of the earliest examples of monumental megalithic architecture in the Americas," she explained.

Chirinos Ogata added that monumental architecture is fundamental to many aspects of human social organization and the development of social complexity, yet the driving forces behind its origins remain poorly understood.

"This type of architecture is deliberately built to be larger and sometimes more elaborate than necessary for its intended function. The world's oldest ceremonial monumental architecture—whether represented by alignments of megalithic stones, large platforms and buildings, or enclosed plazas—was the result of community or corporate actions by groups larger than immediate households and often larger than the local area's population," she argued.

5) How the inhabitants of Kotosh lived

Following its reopening to tourist visits in March, archaeological research in Sector VI of the monumental archaeological zone of Kotosh, located in the Huánuco region, revealed insights into how the people who occupied this sector lived over a 200-year period.

Sector VI is the only area in Kotosh with evidence of permanent human occupation and domestic use. Its inhabitants frequently visited the famous Temple of the Crossed Hands to worship their gods.

This information was shared by archaeologist Peter Romero Sánchez of the Decentralized Directorate of Culture of Huánuco, who was responsible for research during Seasons 2 and 3 of the Archaeological Research Project titled “Recovery of Sector VI of the Monumental Archaeological Zone of Kotosh for Research, Conservation, and Enhancement.”

He explained that domestic occupation in Sector VI is evident from the materials recovered from small workshops where a variety of activities took place. These included the production of domestic artifacts such as pottery (vessels, needles, awls, and others), lithic tools (stone implements such as mortars), hunting and fishing tools, and more.

Sector VI emerged between the years 0 and 200 CE, covering an area of 26,000 square meters. It is located approximately 200 meters southwest of the core area of the Kotosh archaeological site, where nearly 300 excavations have been conducted, covering most of the area. Situated on the highest terrain of the archaeological site, Sector VI was the least studied until recently.

"Sector VI is the largest of all the areas within the monumental archaeological zone of Kotosh and has been the most extensively excavated. The tourist circuit in this sector spans 1.9 kilometers, significantly longer than the circuit in the monumental zone where the Temple of the Crossed Hands is located, which measures 900 linear meters," Romero Sánchez noted.

6) Revelations about a 3,000-Year-Old religious temple in Puémape

After 34 years since the first excavation and study of the Puémape archaeological site, located in the district of San Pedro de Lloc in the La Libertad region, researchers from the Chicama Archaeological Program have found new evidence about the religious temple built approximately 3,000 years ago by the Cupisnique society and the cemetery that was later established in the same area during the occupation by the pre-Inca Salinar culture.

Archaeologist Henry Tantaleán, director of the Chicama Archaeological Program, sponsored by the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM) and the Peruvian Institute of Archaeological Studies, exclusively revealed to the Andina News Agency that the new interventions at Puémape, which began in early March, led to the discovery of stone walls built by the Cupisnique culture in the temple.

These were followed by later burials dating to the Salinar period, a pre-Hispanic culture that developed along the coast of Áncash and La Libertad regions between 500 BCE and 200 CE.

He stated that, according to initial estimates, the Puémape temple was built between 1,000 and 800 BCE by the Cupisnique society, making it contemporary with the early stages of the Chavín culture.

He added that the evidence suggests the temple was occupied for at least 100 years before being abandoned, seemingly due to catastrophic events caused by the El Niño phenomenon along the Peruvian coast.

“It is a square-shaped temple with dimensions of 18 meters per side, built as a half-meter-high platform made of yellow clay brought from a distant location. It features a central staircase oriented 10 degrees north, and on the sides and the back of this U-shaped platform, walls were constructed using stones brought from the beach area as well as nearby hills, standing 1.50 meters tall. These walls were covered by three meters of sand,” he described.

He argued that this temple was a space for ritual use, where, according to the hypothesis proposed by Tantaleán's team, worship ceremonies and body preparations for burials were carried out.

He also noted that the temple's occupation lasted at least 100 years, with a maximum of 200 years. “Afterward, this society collapsed, and the temple was quickly abandoned, seemingly due to the effects of the El Niño phenomenon. Some parts of the structure were destroyed, particularly the floor and the staircase. About 400 to 500 years later, after the temple was naturally covered by sand, a community associated with the Salinar culture settled near the temple and also used the site for burials, even breaking through the floor of the Cupisnique temple,” he explained.

7) Millenia-old ceremonial center unveiled in Apurímac

In April last year, a team of researchers led by archaeologist Edison Mendoza discovered a ceremonial center from the Formative Period, approximately 3,000 years old, in the rural town of San Juan Bautista, located in the district of San Antonio de Cachi, province of Andahuaylas, Apurímac region.

The site, known as the Markayuq ceremonial center, consists of a square platform measuring 31 x 31 meters and approximately four meters high, with an entrance on its northern side. A seven-step staircase was also found at the location.

In an interview with Andina News Agency, Mendoza explained that the ceremonial center was situated atop the Markayuq plateau on an artificially elevated platform and is oriented toward the sacred apus (mountain deities) of Apurímac.

The archaeologist further noted that within the ceremonial center, a rectangular sunken plaza was discovered. He affirmed that the site's characteristics indicate its use for ritual activities. "This was a ceremonial center. From here, one can view a vast horizon," he stated.

The researcher also highlighted that the archaeological site is located in the Pampas River basin, an area home to other significant archaeological complexes.

8) Evidence of Ichma and Inca presence in the middle valley of the Rímac River

A groundbreaking excavation at the Cobián archaeological site, located in the Lima district of Chaclacayo, has revealed the Ichma and Inca occupational sequence of the area. This was determined through identified architectural patterns and unearthed evidence, shedding light on how the inhabitants of this pre-Hispanic settlement lived in the middle valley of the Rímac River.

In April, Gina Marrou, director of the Huaca Cobián Archaeological Research Project and lead investigator at the site, stated in an interview with Andina News Agency that the archaeological site encompasses more than 50 stone structures distributed over an area of 22 hectares. To date, less than 5% of the total area has been excavated, focusing on three complexes in the northern sector of the site, as fieldwork only began in October 2023.

The Cobián archaeological site is located in the Alfonso Cobián residential area, from which it derives its name, at kilometer 21 of the Carretera Central. It is situated past the Ñaña residential area and before the El Cuadro condominium, in the district of Chaclacayo. The human settlement was built on elevated terrain in front of a hill in the upper section of the Alfonso Cobián area, on the left bank of the Rímac River.

Marrou highlighted that the first findings at the Cobián site include a set of semi-circular structures clustered together and interconnected by stairways, corresponding to an initial occupation by the Ichma culture.

“In a second occupation, under Inca domination, we observe that these structures with this settlement pattern begin to change. Modifications were made, adopting rectangular layouts that were better defined and associated with larger patios,” she explained.

“There is no monumental architecture at the Cobián archaeological site, and the constructions were made with stones extracted from nearby hills,” she added.

The excavation also uncovered organic remains, such as corn cobs, beans, fruits like lucuma, and cotton.

Additionally, evidence of trade with other coastal populations was found, including marine products (shells, mussels, crabs, among others). “This indicates economic interaction and product exchange. We also discovered riparian ecosystems, such as reeds and other vegetation, which shed light on the utilization of the valley’s fertility and surrounding areas,” Marrou noted.

Other domestic artifacts unearthed at the Cobián site include fragments of Ichma and Inca ceramics, revealing dual occupation of the area.

“The first occupation corresponds to the Late Intermediate Period, evidenced by the presence of the Ichma culture, while the second occupation occurred during the Late Horizon, under Inca domination, as shown by architectural renovations adopting an orthogonal pattern,” she explained.

The archaeologist also reported the discovery of skeletal remains of two individuals in burial spaces. These remains will be analyzed to determine their sex, age, and other characteristics. “The skeletal remains are incomplete and appear to have been affected, possibly by mudslides during the rainy season or by looting, which has also been documented at other archaeological sites,” she concluded.

9) Mochica geoglyph in the Virú Valley

The use of modern technology in research processes has enabled Peruvian archaeologists to discover a geoglyph that may be associated with Mochica water collection wells in the expansive Virú Valley, located in the La Libertad region. Much of the evidence of pre-Hispanic settlements in this area is often lost among the agricultural fields where agro-industrial companies cultivate blueberries, avocados, asparagus, artichokes, and other crops.

In May 2024, Feren Castillo Luján, director of the Virú Valley Archaeological Project (PAVI), reported that the geoglyph was identified through the analysis of images captured during low-altitude drone mapping across several areas of the Virú Valley. During the review phase, it was noted that a geoglyph had been recorded in an area near a ravine.

Castillo described the geoglyph as measuring 40 meters by 30 meters, with its full form visible only from the air. It is shaped like a falcon and oriented toward the mountain.

The researcher, also a professor at the National University of Trujillo and an affiliate of the Université de Rennes in France, emphasized the significant concentration of Mochica ceramic remains found in the areas where the geoglyph was drawn. Additionally, numerous water collection wells have been identified in various parts of the site, suggesting a potential connection between them.

"It is plausible that the Mochica used a ravine in the Virú Valley to create geoglyphs associated with water collection wells, possibly during periods of drought or heavy rainfall," Castillo proposed.

10) 4,000-year-old temple discovered in Zaña

In June 2024, archaeologists reported the discovery of a temple over 4,000 years old in Zaña Valley, Lambayeque region, contemporaneous with the famous Ventarrón huaca, known for the oldest murals in the Americas.

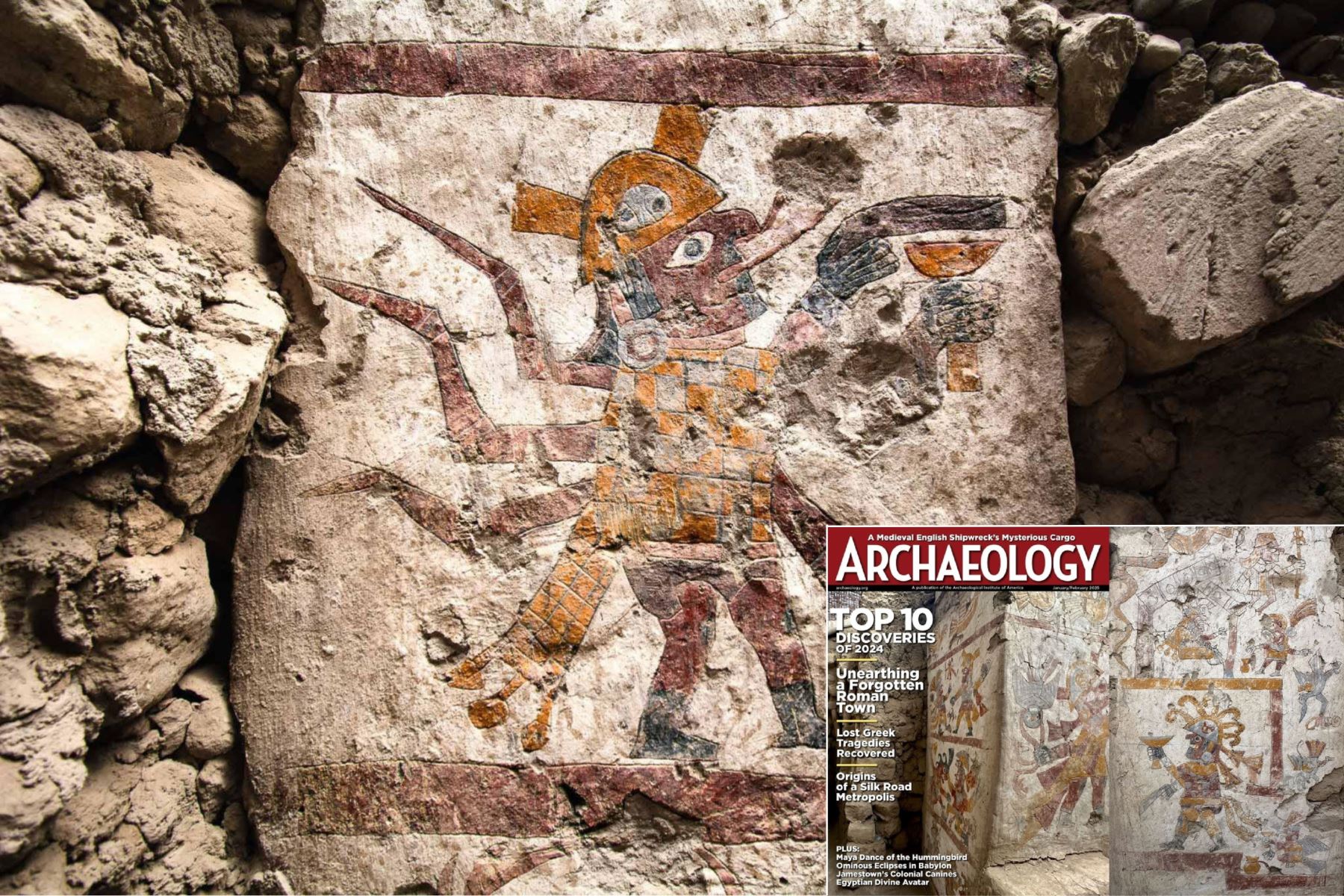

This find, regarded as one of the most significant of 2024 by Archaeology Magazine, was led by researchers from the Cultural Landscapes of Úcupe–Zaña Valley Archaeological Project, directed by Dr. Luis Armando Muro Ynoñán.

"This is the first archaeological project to conduct systematic research at this site, which had no prior references in archaeological records nor previous scientific excavations," emphasized Dr. Muro.

The excavations focused on the Los Paredones de la Otra Banda-Las Ánimas archaeological complex, located in Zaña District, 48 kilometers southeast of Chiclayo, the capital of Lambayeque.

"Our work concentrated on two areas near Las Ánimas hill, characterized by its desert environment and flanked by a vast algarrobo forest, or dry forest, adjacent to the hill," Dr. Muro explained.

In one of the excavation units, a square area measuring 10 meters on each side, researchers uncovered what appears to be the façade of a Formative Period temple, estimated to be 4,000 years old. This age, pending confirmation through radiocarbon analysis, features architectural and decorative elements predating the Chavín culture.

One of the temple's friezes depicts a mythical being with a human-like body, but with a bird’s head and appendages extending from its rear. The figure also has reptilian arms and legs with claws.

"This mythical being seems to be part of a pantheon of deities central to the religion developed between 2,000 and 1,000 BCE, during the Initial Period. This predates Chavín by approximately 1,000 years. It seems that the Chavín religion later adopted these mythological figures, refining them in temples along the coast and ultimately consolidating them at Chavín de Huántar in the highlands of Áncash," Dr. Muro elaborated.

Another adobe slab, believed to depict the same mythical being, was found broken and incomplete on the opposite side of a severely damaged staircase. The damage is attributed to looting, an ongoing issue in the region.

In addition to the temple and its religious imagery, archaeologists discovered part of a perimeter wall decorated in white, black, and blue, adding further significance to this extraordinary find.

11) Mural and throne depicting Mochica female authority among top discoveries of 2024

The remarkable discovery of a throne and murals depicting a prominent female figure in Mochica society by archaeologists from the Pañamarca Cultural Landscapes Archaeological Project has been recognized as one of the most significant archaeological finds of 2024 in Peru and ranks among the top 10 globally, according to Archaeology Magazine.

The discovery took place in July 2024 at the "Moche Imaginary Room" within the Pañamarca archaeological site, located in Nepeña Valley, Santa province, Áncash region, approximately 35 kilometers northwest of Chimbote.

Jessica Ortiz Zevallos, director of the project, explained that the mural, fully uncovered last year after initial work in 2022, features a female figure—possibly a priestess—accompanied by four to five smaller male figures presenting offerings. "This scene suggests her significant role within the Moche ideology in Pañamarca," Ortiz noted.

The adobe throne, found in the same room, is surrounded by walls and pillars that depict four distinct scenes of this powerful woman: receiving visitors in procession, seated on the throne, and other ceremonial contexts.

In earlier research seasons, numerous painted surfaces were documented in the room, including depictions of elegantly dressed men and women, warriors with features of spiders, deer, dogs, and snakes, as well as mythical battles involving Moche heroes and their marine adversaries.

The murals unveiled in July depict rare scenes, such as a workshop of women spinning and weaving, and a procession of men carrying textiles and the crown belonging to the female leader, complete with braided hair. The murals associate the woman with symbols like the crescent moon, the sea and its creatures, and the arts of spinning and weaving.

Ortiz emphasized the ongoing debate among scholars regarding whether the woman is human (a priestess or queen) or mythical (a goddess). "Physical evidence from the throne—including erosion on the backrest, green stone beads, fine threads, and even human hair—clearly indicates it was used by a living person. All evidence points to a female leader of Pañamarca in the 7th century," she concluded.

12) Discovery of artisan city confirmed in Licapa II

The discovery of a complete skeleton belonging to an adult woman at the Licapa II archaeological site in the La Libertad region, in July 2024, has confirmed that the area served as a settlement for skilled artisans. This finding sheds light on the lives of non-elite members of Mochica society.

The human remains, estimated to date back to around 500 A.D., were unearthed in a rectangular adobe funerary chamber beneath the excavation area by researchers from the Chicama Archaeological Program of the National University of San Marcos, led by Henry Tantaleán and Carito Tavera. Licapa II is located in the northern sector of the Chicama Valley, in the district of Casa Grande, Ascope province, approximately 10 kilometers from the renowned El Brujo complex.

The archaeologists described the skeletal remains as belonging to a woman aged 25 to 30 years, positioned supine (on her back) with her skull oriented southward and feet northward, consistent with typical Mochica burial patterns. Alongside the skeleton, three smooth copper sheets were found—one placed over the mouth and the others in each hand.

"Placing objects in the mouths of the deceased is a common practice in Moche burials, from elites to lower social strata," Tantaleán explained. He hypothesized that the copper sheets were likely unfinished artifacts, intended for further crafting or as part of other metallic items, serving as ritual offerings in a ceremonial renewal of the space.

This discovery reinforces the evidence that Licapa II was a hub for diverse artisanal activities, including ceramics, textiles, and metallurgy, providing a richer understanding of the Mochica's specialized labor economy and the lives of their artisans.

13) Sicán inhabitants took care of their domestic animals

The inhabitants of the Sicán or Lambayeque culture maintained a close relationship with the animals they raised, particularly canids and camelids (dogs or wolves and llamas), specialists from the University of British Columbia, Canada, revealed in September 2024.

This has been evidenced by the care provided for the recovery of bone pathologies (fractures) in some of these animals. Thus, these zooarchaeological findings suggest a significant concern for the well-being of the animals in their environment.

Researchers from the National Sicán Museum and Canadian archaeologists, led by Aleksa Alaica and Luis Manuel González, conducted an exhaustive review of organic material, particularly bones and mollusks, documented by the Archaeological Intervention Program of the Pomac Forest Historical Sanctuary (PIAP).

One of the main objectives of the research project was to determine the relationship between human populations and animals during the pre-Hispanic era.

14) Decorated Mochica walls in Huaca Mochan

A series of plastered walls in red, yellow, and white, as well as evidence of other surfaces decorated with geometric designs and animal depictions, such as snakes, "life" fish, and octopuses, were uncovered by archaeologists from the National University of Trujillo (UNT) on the eastern side of Huaca Mochan, located in the Calunga sector, in the province of Virú, La Libertad region.

Feren Castillo Luján, director of the Virú Valley Archaeological Project (PAVI), reported the discovery of fine ceramics, textiles, and other elements confirming that this pyramid-shaped structure was, in fact, a temple used by the Moche for their religious ceremonies.

According to the researcher, this finding refutes the idea that Huaca Mochan, built approximately between 400 and 800 A.D., was part of the Virú and Gallinazo cultures.

The UNT professor also stated that, based on the evidence, the use of adobe bricks made with cane molds, previously associated with the Virú or Gallinazo culture, must be better reinterpreted.

"Archaeologists rely on preserved material culture, such as ceramics, and here (at Huaca Mochan), there is abundant evidence of Mochica ceramics," noted Castillo, whose research is part of his PhD thesis at the Université de Rennes, France.

15) Life in Cusco before the Incas

An investigation at the Hatun Q'ero archaeological site, located at 3,750 meters above sea level in the present-day district of Pomacanchi, in the Cusco province of Acomayo, revealed in September last year its first results, shedding light on the life of the Qanchi society that inhabited this region before the rise and dominance of the Incas.

The study, conducted by a team of archaeologists from the National University of San Marcos, led by Pieter Van Dalen, indicates that the archaeological site contains evidence of habitation 1,000 years ago and dates back to the Late Intermediate Period.

"The Qanchis flourished during the last phase of the Wari presence in the area. This culture developed between the years 1000 and 1430 when they were subjugated by the Incas and became part of the Tahuantinsuyo until 1533 with the arrival of the Spaniards. They remained in this condition until 1560 when the law for the reduction of indigenous towns was enacted, leading to the creation of the town of San Agustín de Pomacanchi," he explained.

The archaeologist clarified that the excavation site was an alluvial terrace near the Pomacanchi lagoon, the third largest in Peru after Titicaca and Chinchaycocha. This lagoon was considered a deity by the ancient local cultures.

He stated that this terrace was a ceremonial area dedicated to offering tributes to local deities. "Llamas or alpacas were sacrificed to ask the deities to multiply livestock production," he noted.

The Pomacanchi lagoon was a deity for the Qanchis and other nearby cultures such as the Lupaca and Cusco. Over time, it became a principal huaca (sacred place) of the Tahuantinsuyo.

Van Dalen mentioned that the Qanchi culture, being a local society focused on agriculture (evidenced by the presence of terraces) and livestock farming, left traces of this way of life. In the terraces, they cultivated potatoes, oca, mashua, and other crops.

16) Geoglyphs discovered using AI are older than the Nasca lines

In September 2024, the Ministry of Culture announced that the 303 new geoglyphs discovered in the Pampa de Nasca by scientists from Japan's Yamagata University, with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI), are older than the iconic Nasca Lines, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994.

The discoveries include anthropomorphic (human-like) designs, as well as a smaller number of animal motifs native to the region and other figures. These geoglyphs are located near paths and trails crossing the Pampa de Nasca and were created using both high and low relief techniques. They are usually grouped and are smaller in size compared to the famous Nasca Lines.

The new geoglyphs were found on the slopes and hills of the Pampa de Nasca. Their identification was made possible through the use of drones and artificial intelligence, which allowed researchers to outline the figures with greater precision.

The Ministry also noted that, through the Decentralized Directorate of Culture of Ica, it oversees ongoing work that began in 2010 and continues to unveil new figures in the Pampa de Nasca. The use of AI, applied by researchers from the Nasca Institute of Yamagata University in collaboration with IBM Research, has doubled the number of known figures, marking a new chapter in the understanding of these monumental lines.

17) Funerary bundle with complete burial set in the Ica desert

Four funerary bundles from the Ika culture, over 800 years old, were unearthed at the archaeological site of Huacachina Seca, formerly known as Soniche, located in the Pueblo Nuevo district, in the province and region of Ica. One of these bundles is covered with textiles and accompanied by its funerary artifacts.

The preservation state of the funerary bundles is described as "fair to good" due to the sandy and dry terrain where they were discovered, explained Rafael Mallco Huarcaya, who leads the team of archaeologists conducting the research.

“In the funerary bundles, we found gourd containers and remains of maize. The presence of ash accumulations as offerings and a significant amount of maize husks forming part of the fill that covered this important find indicates the sacred use of Huacachina Seca (Soniche) during the Late Intermediate Period,” he added.

He explained that the discovery demonstrates the Ika culture's deep respect for their dead, irrespective of social class, ensuring they were remembered and treated properly after death.

“The archaeological evidence being uncovered confirms that Huacachina Seca was one of the most important cemeteries of the Ika culture. It is possible that it served as a burial site for curacas and individuals from the administrative center of Takaraka. This site merits special attention in its study as it will allow us to understand the characteristics of a society that inhabited the Ica Valley prior to the Inca arrival and Spanish colonization,” he stated.

18) Human burials at Huaca Poncoy 2 in Lambayeque

In October of 2024, specialists from the Lambayeque Decentralized Directorate of Culture (DDC) registered and recovered three adult burials during an emergency operation at the Huaca Poncoy 2 archaeological site, located in the Monsefú district, Chiclayo province.

Additionally, textile materials, mollusk remains, camelid bones, ceramics, fragments of mural paintings, wooden artifacts, and metal objects were discovered.

The recovery of the burials and associated materials will not only aid in identifying certain occupational patterns or dynamics at the site and its cultural affiliation but also foster integration and awareness among local populations regarding the protection and preservation of archaeological sites. This initiative aims to support sustainable research contributing to the economic and social development of the surrounding communities.

The Huaca Poncoy 2 archaeological site consists of a pre-Hispanic mound and attached platforms located to the south and west. Evidence suggests the site dates back to the Late Intermediate Period (900 A.D.–1440 A.D.).

19) New discoveries about Pacopampa to better understand this ancient culture

In November, new funerary contexts were revealed during the latest excavation season at the Pacopampa Archaeological Complex, located in the Cajamarca region.

The findings include figures of medium importance, not reaching the rank of the Priest of the Pututos or the Priest of the Seals—key religious leaders of this culture discovered in 2022 and 2023, respectively. However, these discoveries will help refine the chronology of this culture.

Archaeologists Juan Pablo Villanueva and Daniel Morales, collaborating with Japanese archaeologist Yuji Seki, specified that the discoveries were made in an area known as La Capilla.

“(...) we began our research aiming to understand the chronology of the discovered tombs and the architecture of this significant ceremonial complex, Pacopampa. We excavated in various areas to uncover relationships, and near the two funerary contexts, we found a tomb containing a figure alongside two ceramic bowls. This individual is of medium rank, not at the level of earlier discoveries. The Lord of the Pututos had 20,000 ceramic bowls,” Villanueva emphasized.

In an interview with Andina News Agency, the researchers and professors from the National University of San Marcos reiterated that the findings occurred in La Capilla, “a smaller structure compared to the main building of Pacopampa, but very significant because it provides insight into the early phase of this culture and helps refine the timeline of its development.”

Villanueva stated that, in addition to the funerary context, they found platforms bordered by retaining walls, which represent evidence of early Pacopampa architecture, dating back to 1,300–1,200 BCE.

Alongside this individual, the archaeological team discovered five other funerary contexts belonging to different phases of the culture, which spanned from 1,300 to 700 BCE. “Some of these figures belong to the early Pacopampa IA Phase, while others are from Phase IB. One individual was found with a necklace featuring a chrysocolla pendant, while two others had ceramic bowls placed as offerings over their skulls, respectively. A particularly noteworthy case from the Pacopampa II Phase revealed a figure with a copper pin, evidence of early copper artifact production in the central Andes,” Villanueva noted.

The San Marcos researcher explained that the funerary contexts are closely related to the temple’s early architecture. “During architectural renovations of this structure throughout Pacopampa's construction phases, these contexts were placed, in at least one instance, as part of a ritual to imbue energy into the new constructions. In Andean cosmology, bones are placed at the bases of bridges or other structures to strengthen them,” he stated.

20) Elite figure linked to cacao found in Montegrande

A recent discovery in November at the Montegrande archaeological site, located in the district and province of Jaén, Cajamarca region, revealed the tomb of a high-ranking religious figure buried at the center of a spiral-shaped temple. This finding is accompanied by evidence of the world’s oldest cacao, dating back 5,300 years.

Archaeologist Quirino Olivera, who discovered this religious monument, told Andina News Agency that work is currently focused on removing the second ring of the spiral. “It’s a complex process; we need to reach over three meters in depth to locate the tomb of the temple’s most significant religious figure,” he stated.

Olivera explained his hypothesis, suggesting that the tomb belongs to a woman associated with cacao.

“The spiral-shaped architecture, covering 400 square meters, anthropomorphically represents a woman in labor. Her lower limbs encompass the entire spiral, with the tomb situated at the center in a fetal position, as if inside a womb. From her head, the spiral extends outward in a counterclockwise direction, symbolizing the soul’s journey after death to the afterlife. It’s truly a stunning discovery,” he emphasized.

The archaeologist added that the figure seems oriented toward the sunrise and that this may be the tomb of the most significant religious figure excavated in the Americas linked to a woman, with an estimated age of 5,300 years. However, it is possible that this date could be revised to 3,300 years before the present.

“I am referring to the Marañón culture, a cultural development that emerged in the Marañón Valley, where major rivers such as the Chinchipe and Huancabamba converge as they descend from the mountain range,” Olivera noted.

21) Discovery of the Wari Alpaca Route at the Llaqtapampa archaeological site

In November, Ayacucho archaeologist and professor Nils Sulca announced the discovery of the Wari Alpaca Route at the Llaqtapampa archaeological site, located in the Ayacucho region.

The specialist, a faculty member at the Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga, explained that this route was essential for providing food to the population of the Wari capital, the first empire of South America and predecessor to the Incas, which had a population of up to 20,000 people.

Sulca noted that Llaqtapampa served as a link between the coast and the highlands. It is located at an altitude where only ichu grass, a type of Andean pasture, grows, which is ideal for feeding and raising camelids.

The archaeologist explained that he and his team are working on two twin complexes named Llactaqapampa 1 and Llaqtapampa 2, focusing their efforts on one of them. Preliminary findings suggest the site may have been used as a corral for a large number of camelids.

Sulca emphasized that the Wari carefully selected the landscapes for their settlements, prioritizing "water springs" or sources of water to sustain both livestock and human populations. Llaqtapampa is no exception, as it is located near three lagoons.

(END) LZD/JMP/MDV

Published: 1/3/2025